- Health in Perspective

- Posts

- Health Polarization in the US

Health Polarization in the US

An Opinion About the Present and Future

After reading my articles for the past several months, you may have noticed a glaring omission. It seems that every time we check the news or find new data about health, that data is supplemented by a political agenda or controversy.

That made me think - what causes health politicization? Is it reversible? You might wonder, why would I focus one of my health policy articles which have generally been medicine focused and global in scope on health politicization in the US? I believe that we have reached a tipping point in the nation where politicization has resulted in misinformation, actively worsening healthcare outcomes for millions. While we are seeing generalized extreme polarization on nearly every issue, the fact that this polarization is affecting health policy is disturbing to say the least. Polarization has resulted in the mass consumerism of mis- or dis-information (which I will explore later in this article) contributing to real people misunderstanding their own health needs and voting for policies that may actually hurt them.

While many individuals and institutions have begun opposing the rise in mis- and disinformation in recent years (and I do support this trend), I want to discuss why, in my opinion, these efforts have produced little if any change. So, does “fact checking” really work?

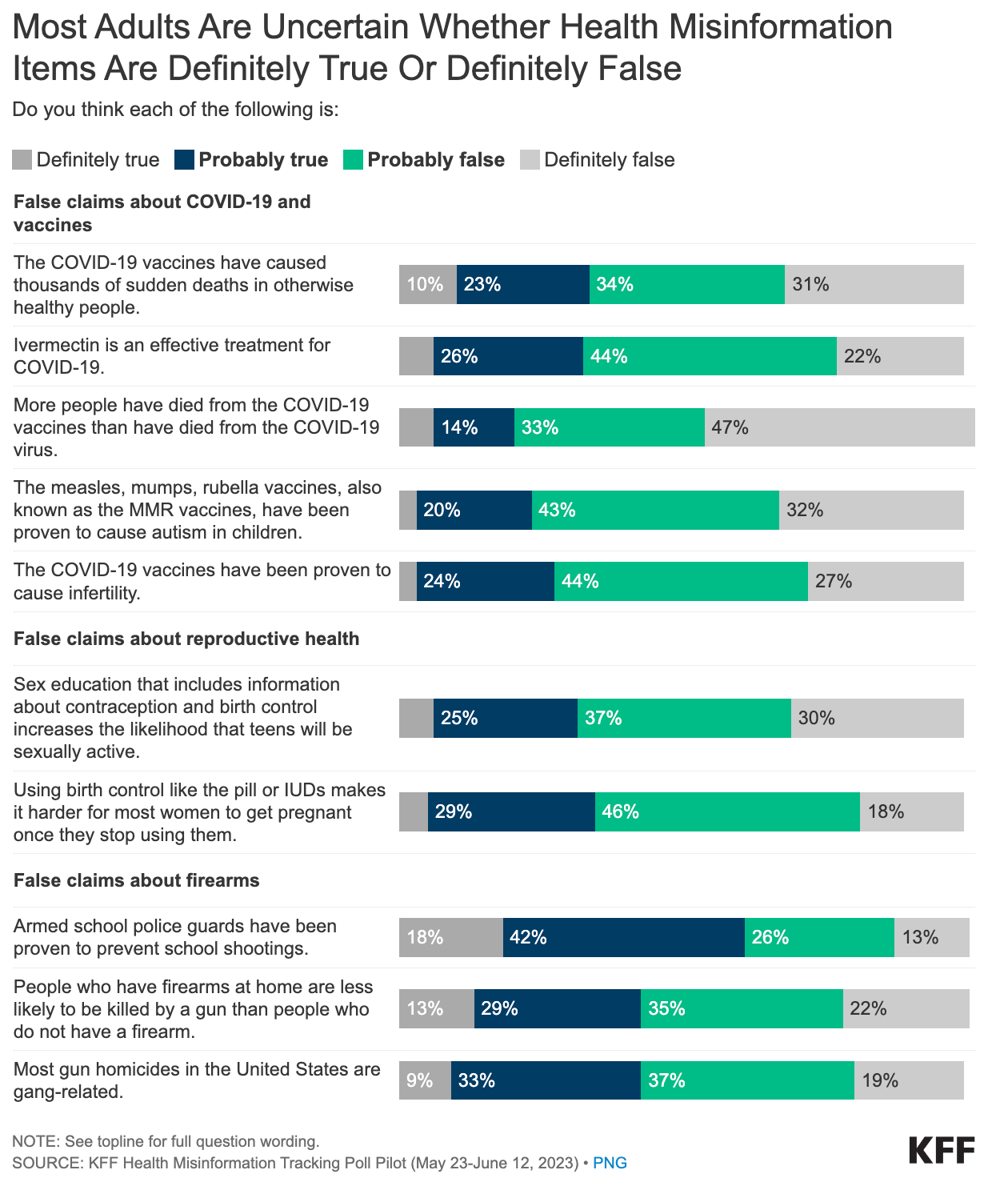

We find most of the information we consume through various news articles (CBS, FOX, CNN, etc.) and through social media. Instagram, Twitter, and various other media platforms have been placing “fake news” labels on certain posts, warning users that the content they are consuming is likely inaccurate or a distortion of the truth. You would think, considering that there are roughly 170 million American Instagram users, that these measures are having great effect, but a recent KFF survey finds that 40% of Americans have heard at least one false claim about COVID-19, reproductive health, or gun violence (highly polarized health issues). (1, 2)

Why might this be the case? When reading an article, if empirical data suggests something you may not necessarily believe, and then a vocal news critic argues against that data, supporting your viewpoint, who do you believe? I argue that this deep mistrust in institutions is a uniquely American trait. We characterize institutions in power in a way that serves our own interests; many who do not agree with the CDC’s perspective argue that the institution is political, power-seeking, and pushing forth a “radical” agenda. In fact, I posit that the main reason mis- and disinformation exists at all is because of this distrust towards the agencies that are in charge of health research and policy. Thus, fact checking only works when individuals trust the fact-checker over the source of the information. We almost always receive information from people and sources we trust and because [1] we likely trust the fact-checker less and [2] we prefer to believe that our trusted sources are right, we often disregard fact-checks entirely.

Is there a way to separate institutions from the policies and political agendas they may be related to? This is a topic I hope to explore further in this article, but first I hope to describe this “uniquely American society” I mentioned previously. Our society is “uniquely American” in that it is structured around individualism and personal distrust of institutions and people in power. Need evidence? Take a look at this chart showing Americans’ trust in the pre-eminent authorities on health. The fact that 33% of Americans distrust the CDC and 34% distrust the FDA signals that Americans have little faith in the very organizations that make decisions about their health.

Healthcare in the United States is something of a black box; non-providers and non-legislators know little to nothing about how healthcare programs are structured and organized. This is one of the reasons why I started this journal in the first place: to bring transparency to an especially important field that is too often disregarded by popular media. This lack of information about health issues coupled with a lack of healthcare access results in people developing their own narratives. These narratives more often than not run counter to the mainstream flow of information and contribute to the rise of mis- and disinformation I mentioned earlier.

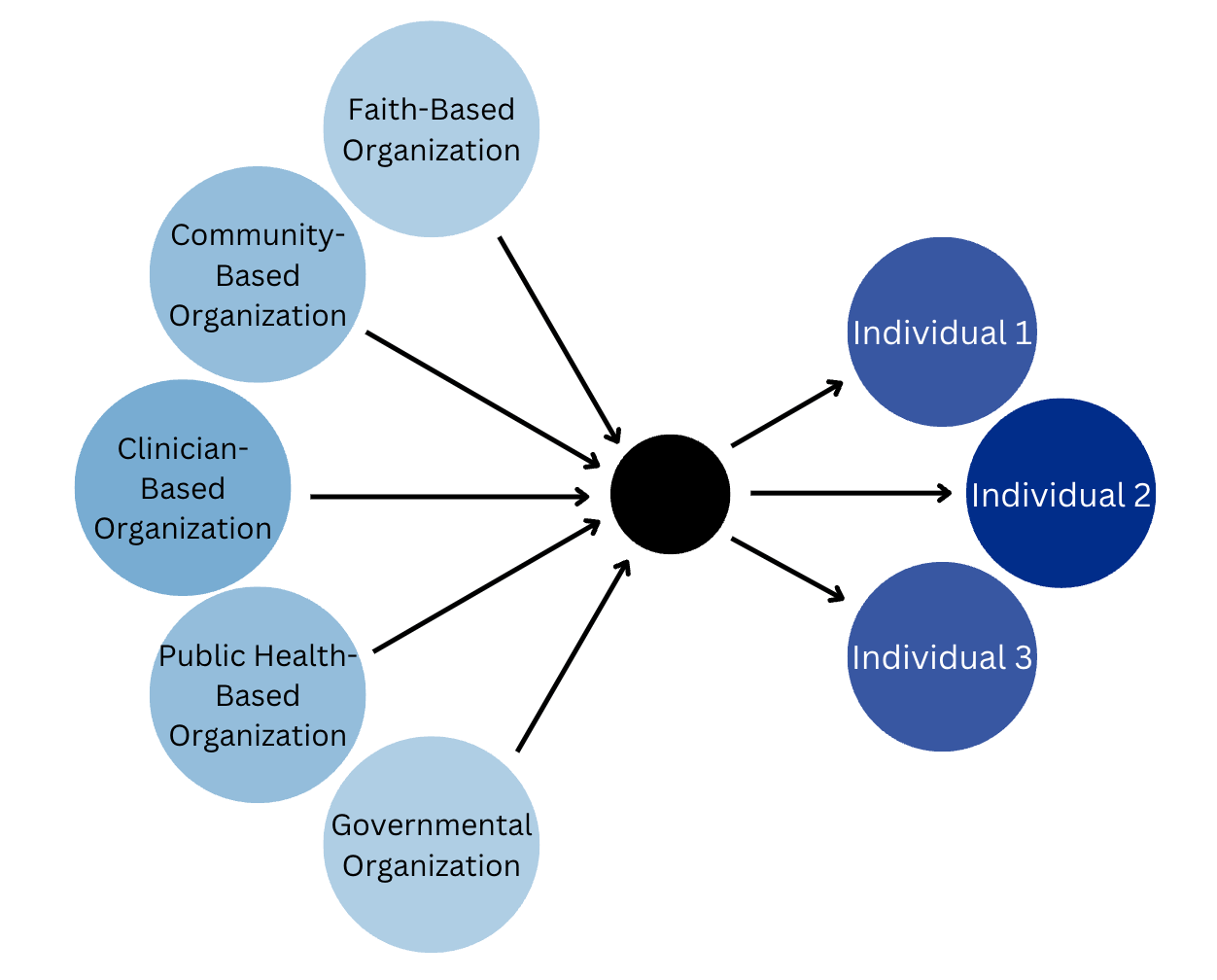

I argue that this confluence of factors (lack of information, lack of healthcare access, uniquely American traits of individualism and distrust of authority) creates a culture of distrust. Our main point of contact with the healthcare system in America is our primary care provider, whom we meet with for maybe 30 minutes to an hour during our annual check up. Throughout the rest of the year, we are inundated with streams of sometimes contradictory information from faith-based, community-based, clinician-based, public health-based, and governmental organizations. Who do we choose to believe? Most if not all of these perspectives are grounded in reality, but for the average American who has little time to wrap their head around these issues, these streams of information are excessive. In short, I believe a more unified health approach is necessary.

Americans vote based on health issues. Health issues, including mental health, data privacy, equity, and reproductive health, are so predominant in modern day politics that politicians are willing to stake their careers on a particular viewpoint. (3) However, I argue that politicians have taken up views that reflect the ideas and opinions of their stakeholders rather than their own perspectives. Thus, health policy votes break along party lines (meaning that almost every member of each political party votes the same way), exacerbating political polarization. Take a look at how the political right and left have approached science funding over the past 2 decades: (4)

If US politics continues its current trajectory, the divide between the left and right will only widen. If health policy is tied to the general political landscape, it seems that there is no foreseeable end to this crisis. Is this even a policy issue and if so how can legislators attempt to tackle this crisis?

In her article titled “How Do People Know What Health Information to Believe?”, Dr. Panthagani discusses how we can tackle the rise of mis- and disinformation at the consumer level. (5) By treating information as a commodity with patients as consumers, we can curb the rise of “fake news” as we would any other harmful good: through education. Through health communications research, Dr. Panthagani argues that we may empower members of the public to make educated decisions regarding health information. She argues that providing patients with the means to distinguish between empirical evidence and misconstrued fact is more valuable than endless fact checking. I support Dr. Panthagani’s argument and believe that changes should be made at the policy level as well. By increasing health and public health literacy, patients will develop the means to care for themselves without being diverted by misinformation. Furthermore, by streamlining the information process (not by reducing information but by using direct channels), we can provide American individuals with accurate information without overwhelming them in the process.

I believe that by establishing a legislative health body that is isolated from general politics and by combining existing streams of communication, we can provide American individuals with a better understanding of the healthcare system and how to effectively seek care when needed. Ultimately, health polarization did not start last year or even last decade, and it is unlikely to end even in the next 25 years; perhaps a more unified legislative approach that fully realizes the “health” in “health policy” will save lives in the long run.